Hotlinks

Friends of the Site

Reach out to me!

mdkerrig@gmail.comSite Index

My Top Five Posts

September 2023

Table of Contents

- 09/10 – Wheeler Peak

- 09/14 – Winterizing Ella Mountain – Retrospective

- 09/15 – Prometheus

- 09/16 – Petrified Forest National Park

- 09/21 – Mt. Mitchell, Base to Peak

- 09/30 - How to Get a Job in Antarctica – An Onboarding Timeline

Wheeler Peak

2023.09.10

Mountain monardella (Monardella odoratissima, Lamiaceae), also known as coyote mint.

What I believe to be smoothleaf penstemon (Pensetemon leiophyllus, Plantaginaceae).

Between the violet blooms popped some kind of rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus sp., Asteraceae) with brilliant yellow.

Some kind of blackberry (Rubus sp., Rosaceae).

What looks to be some kind of cinquefoil (Potentilla sp., Rosaceae). These grew past the other blossoms, right to the treeline.

Eventually you reach the top and have a 360-degree view of the surrounding landscape, a truly beautiful spread of the Nevada landscape. Below you, the glacier rests above a grove of Bristlecone pines.

I suggest opening this in another tab and zooming in on this near-360-degree view from Wheeler peak.

Looking North. From left to right: Stella Lake, Teresa Lake, and Blue Lake.

The peak serves as one of the best lunch spots in the state, and it was there that I "enjoyed" a crummy MRE Pizza. Review coming soon.

Winterizing Ella Mountain - Retrospective

2023.09.14

To winterize, it was simply a matter of draining the water cistern, removing the pump, disconnecting all electronics, shuttering the windows, taking out linens – little bits of housekeeping here and there to leave it better for the next lookout (me). It was a quick process and bittersweet to shutter up the windows.

One thing I realized only after the summer had ended was that I never once felt bored, antsy, or ready to leave the tower. I felt quite content with my own company and in fact felt like my days off and trips to town were interruptions rather than reliefs. I found a lot of joy in the stretches of solitude and it really felt I like I was in my own pocket of the world.

That's not to say that I was grumpy when visitors would arrive (it was always fun to meet and greet them with fresh-baked cookies, as I kept dough prepared and could see them coming from miles away), as I also had fun getting to know people who came to visit the tower. Most all were offroaders or caravaners, and there was a good mix of people who local to town or southeast Nevada as well as people who came from Utah, California, Washington, the east coast, and as far as Australia. Some were solitary, and some came in groups larger than twenty, but either way it was always a pleasure to have people.

*At the time of writing, March 11 2024, I know that I'm going to be returning to the fire tower to help settle affairs as I return from Antarctica – it'll be a nice breather before figuring out what's next, and I'm already excited to be back at the lookout. This time, I'm bringing a telescope.

While the majority of the summer focused on a lot of things that aren't plants, I appreciate it if you've enjoyed reading this blog that started simply as a way to share photographs with people I know. I do intend to keep posting plants but also just neat things that may or may not be related to plants or the natural world. I don't really want this to be a tourist page but for the first time in my life I am doing a fair bit of traveling and that makes me a tourist. Luckily, there are plants all over, save for the one continent I'm going to next.

Prometheus

2023.09.15

I will not disclose the location of Prometheus, nor will I give hints to its location – that information is not mine to share. If you'd like to see it, go do some digging and start making some phone calls.

Here, I've attempted to map the location of the largest parts of what remains of Prometheus (not to scale/not done with formal measurements).

Petrified Forest National Park

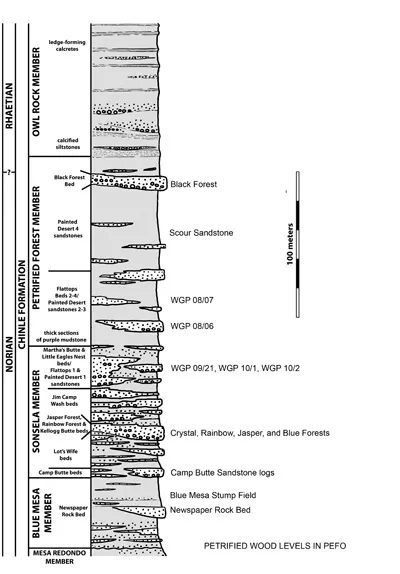

2023.09.16

<

Also present (but not as clearly seen) on the left side of the above image is evidence of fire scarring, a unique part of the history of this log but also an interesting one, given that these trees are thought to have grown in bottomlands where fire would be much less common. It is observed in living trees that some insect species will attack trees that are stressed, and it's possible that this was the case with this particular tree; the fire stressed the tree and made it susceptible to insect infestation.

A more recent addition to this log's story is the fact that evidence suggests it is upside-down! This was likely caused by humans, who would have moved the log to make way for a roadway, back in the early 1900s when this particular part of the park was open to vehicles driving down into the canyon. Thankfully that doesn't happen anymore.

However, the story of the Lithic peoples and Puebo indigenous peoples is not mine to tell. I felt the park did a good job of sharing not only the geologic phenomena of petrified wood but also the history of the people who lived there long before the park was established. The NPS website has a page detailing the different periods of habitation as well as a photo gallery of their legacy, but I suggest further reading if you are interested.

I wish I had had more time to spend in this park to really soak it in, but I was in a rush to get back east before the big hop south. Once again, postcards and a cancellation to wrap up this park.

Mt. Mitchell, Base to Peak

2023.09.21

There are more photos of the plants I had been missing all summer than scenic views, so if you're here for plants I hope you enjoy. The trail starts at the base of Mt. Mitchell at the Black Mountain and makes its way up to the top of Mount Mitchell, the tallest North American peak east of the Mississippi. From bottom to top and back down again it takes 6 or 7 hours, and it's my favourite hike as you can see transisition in forest type from mixed hardwood to heath-oak to spruce-fir to fir.

In no particular order of appearance, here are some of the plants seen along the walk! I neglected to note community type or elevation of incidence for any of these. Forgive and notify me of any misidentifications, as it has been a while since I took these.

Beetleweed (Galax urceolata, Diapensiaceae) with developing fruit towards the start of the trail.

Among the beetlweed grew ground cedar (Diphasiastrum digitatum, Lycopodiaceae), many with strobili!

Running clubmoss (Lycopodium clavatum, Lycopodiaceae) grew among the above as well, though in lesser quantity.

Here is pink turtlehead (Chelone lyonii, Plantaginaceae) in abundance along a small stream that crosses the trail.

Across from the pink turtlehead grew New York fern (Amauropelta noveboracensis, Thelypteridaceae).

American chestnut (Castanea dentata, Fagaceae) peeks out here and there!

We begin to see rock tripe (Umbilicaria sp., Umbrilicariaceae) as rock outcrops become more common in higher elevations.

What I believe* to be deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum var. stamineum, Ericaceae). Fruit was fairly abundant as we hiked.

*This identification is six months after the observation, using limited photos, while in Antarctica.

The larger outcrops didn't stop trees from growing around them, and some went to the absolute extreme growing on top. You may have heard the term "nurse logs", these seem to be cases of "nurse rocks".

Time makes the heart grow fonder but it does not making IDing unknown bryophytes easier.

Eventually, you reach the highest parts of the trail as you transition from red spruce (Picea rubens, Pinaceae, the tall trees in the right of the photograph above) to spruce-fir and eventually Fraser fir (Abies fraseri, Pinaceae, photographed below).

It's in these higher elevation areas where you can find such species as:

Mountain woodsorrel (Oxalis montana, Oxalidaceae – NOT a clover!)

Kidneyleaf grass-of-parnassus (Parnassia asarifolia, Parnassiaceae).

Yellow birch (Betula allegheniensis, Betulaceae), foliage not accessible.

American raspberry (Rubus strigosus, Rosaceae) in abundance, though only some bearing fruit.

And eventually, the top!

Thank you for reading (if you made it this far)!

How to Get a Job in Antarctica

a.k.a.

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Paperwork:

An Onboarding Timeline

June – October 2024

Of course, your mileage can (and will) vary. However, there were many times where I was worried things were taking too long and it helped to have other people's anecdotes. Hopefully this guide helps someone as they work through their own hiring process. It is incredibly lengthy and mostly takes time to get through the Physical Qualification (PQ) packet, with lots of other little bits of paperwork to get through.

The PQ process is an intensive and extensive readout on your health and health history to determine whether it's safe for you to deploy to the ice, where medical care isn't as accessible and you are remote from full-fledged medical centers back in New Zealand. Here is a document detailing what could medically disqualify you (NPQ - Not Physically Qualified) from working in Antarctica.

Upon telling people I was headed to Antarctica, a lot of them asked "how do you even get a job down there?". The short answer: apply and go through the mountain of paperwork required to qualify.

June

June 1

I applied to only three jobs: Postal Clerk (McMurdo), Production Cook (McMurdo), Production Cook (South Pole) through Gana-A'Yoo's website.June 13

Automatic email response, minimum requirements met for Production Cook (McMurdo), requesting confirmation of interest.June 15

Automatic email response, minimum requirements met for Production Cook (South Pole), requesting confirmation of interest. I responded in the affirmative to bothJune 20

Notified by email that my resume was now visible to hiring manager and was under review.June 21 - 21 days after first application

Received an email from the HR Representative, and I scheduled a Zoom meeting with them for the next day.June 22

Zoom meeting with the HR representative. It took ~30 minutes and set expectations for the job. Following the meeting, I was invited to schedule a Zoom meeting with the Head Chef.June 30

Zoom meeting with the Head Chef.July

July 8 - 38 days after first application

I received an email with an Alternate Contract offer – I was not first in line to go but had the potential for a Primary Contract should others drop out or should I show good progress on the PQ packet.Received emails with a Background Questionnaire as well as requests for information regarding my employment history. I completed and submitted these the same day.

July 9

I received my PQ packet by email and scheduled my bloodwork visit.The PQ packet is a daunting and extensive process that makes sure one is healthy enough to travel to Antarctica. Given the limited resources available and the remoteness of the continent, it's important to know the physical health of everyone down there.

July 11

I completed my laboratory blood test, made a visit to an optometrist and updated my glasses prescription, and made a visit to a doctor's office for a complete physical and EKG reading.July 12

I made a visit to a dentist for X-Rays, a panoramic imaging of my teeth, and a small filling. I scheduled a cleaning for two weeks later. The dentist recommended I have my wisdom teeth removed before travel to the ice, and to ignore this suggestion would disqualify me. I scheduled my wisdom teeth for August 7.Completed my urine drug test.

July 26 - 18 days after initial receipt of PQ packet

Completed my dental cleaning.After discussion with people in Denver and UTMB, I submitted my PQ packet despite knowing I had not yet had my wisdom teeth removed. This is done to let UTMB get a head start on review to see if there is anything else outstanding that would be needed. They were aware that my wisdom teeth were still scheduled to be removed and said to send that documentation when the procedure was completed.

July 28 - 2 days after first submission of PQ packet

Received information that my dental and medical information was well-received and in review.Received a request for additional documentation - in this case it was the formatting of one of the signatures my physician made on one of the several pages they were accountable for.

August

August 2

Received feedback regarding the clarity of one of the documents I sent in from my physician. I requested a correction from my physician the same day.Received an email detailing that I would need an updated influenza vaccine in order to deploy. I scheduled it the same day.

August 4

Received the corrected documentation from my physician and resubmitted for review.Received feedback regarding the clarity (in a different way) on the same document.

August 4

Received a second correction from my physician and resubmitted for review. Document well received by UTMB.August 5 - 65 days before I leave my Airport of Departure

Travel forms became available to me. These forms detailed things like what airport I would be leaving from (Airport of Departure – AOD), my identity and passport information, meal preferences, etc. It also requested information for my clothing sizes for Extreme Cold Weather (ECW) gear and what lodging accomodations I would prefer (including asking "Are you a snorer?")August 6

I submitted my Travel Packet for review.August 7

I received confirmation that my Travel Packet was well-received.Today was supposed to be the date of my wisdom teeth removal, but for personal reasons the oral surgeon had to reschedule for August 21.

August 8 - 14 days after first submission of PQ packet

As expected due to a head full of teeth, I was found Not Physically Qualified (NPQ). This email included reasons for the NPQ and what actions (if any) to take to help remedy the situation.August 9

I resubmitted my medical information review detailing why my wisdom teeth were not yet removed.August 14

I received my influenza vaccine and submitted documentation to UTMB the same day.August 15

I received an email requesting another correction on the same document as before. I received a correction and resubmitted the same day.August 16

I received confirmation that the third correction was well-received.August 21

I had my wisdom teeth removed.August 25 - 85 days after first application, 52 days before arrival on-ice.

Received Primary Contract offer (pending successful PQ) following removal of wisdom teeth, before subnmission of official documentation.August 29

I received an onboarding email from the National Science Foundation (NSF). This directed me to request a form called Optional Form 306 (OF306) and a printed card on which to get my fingerprints taken. I responded the same day requesting these items.August 30

I received a link to document OF306. I filled it out and returned it the same dayAugust 31

I received documentation regarding my wisdom teeth removal from my dentist and sent it to UTMB. The same day, I received word that my Dental Information was well-received and once again in review.September

September 3

I received an email requesting I fill out and sign the USAP Polar Code of Conduct and COVID-19 Safety Pledge documents. I signed and submitted them the same day.September 8 - 62 days after initial receipt of PQ packet

I received an email stating that I was officially Physically Qualified (PQ'd) upon receipt of the dental information surrounding my wisdom teeth removal.September 12 - 15 days after outreach from NSF point of contact

I received my NSF Fingerprint Card in the mail and schedule my appointment at a local sheriff's office.I receive an email from an HR representative regarding the Elevated Background Investigation (EBI), questioning whether or not I had received word from my point of contact at the NSF. I replied that I had not, and at the time of writing (2024.03.24, currently still at McMurdo) I have not yet received the email to start my EBI process.

September 15

I had my fingerprints taken at the local sheriff's office and mailed the card with expedited shipping to the NSF office in Virginia.September 18

I receieved confirmation that my fingerprints were well-received in Viringia.September 23

I received an email requesting information for the USAP deployment screening.September 27 - 10 days before I leave my AOD

I received my Travel Itinerary detailing my flight schedule from my AOD to Christchurch. I now had a cemented countdown on when I was supposed to be in Antarctica (two weeks later than expected – my original on-ice date was October 1 but for reasons still unknown to me it was pushed back two weeks).October

October 3

I received my Travel Documents for arrival in New Zealand. These included a letter to airport agents, both domestic and Kiwi, the process I was going through and what allowances were given for things like baggage weight and visa times.October 4

I received documents detailing what my arrival in Christchurch would look like. These included items such as who to look for at the aiport or scheduling for trainings and gear receipt.October 7

I receieved an email regarding the New Zealand traveler declaration form - a sort of pre-customs form asking what goods and materials I may or may not have in my luggage.October 8 - 9 days before my arrival in Antarctica

I depart from my AOD to New Zealand, with several stops along the way.October 11

I arrive in Christchurch, 36 hours after departure and with a full day missing from my calendar due to the fact that I jumped from UTC–05:00 to UTC+12:00. I arrived in the mid-afternoon and after some time getting oriented, I had the rest of the day to myself in Christchurch.October 11

I spent my morning doing self-paced online courses and trainings through Bridge. Following this, I was taken to the Clothing Distribution Center (CDC) to receive my ECW and a COVID-19 test.October 12

The bulk of the monring was spent in online zoom meetings with others who were on the same ice flight as me.October 13

The first three days are all that are scheduled for you in Christchurch, and any delays are your time to use. There was another cohort that was set to fly out 10 days before we arrived but they had been stuck due to weather delays. On days they were delayed, my cohort knew we wouldn't be flying because they were next in line. Today was my first delay day in Christchurch, which I'll document in another post.October 14

Second day of delay in Christchurch. The group ahead of us made it onto the plane but had to deboard due to weather conditions between Christchurch and New Zealand.October 15

Third day of delay in Christchurch. The group ahead of us successfully flew to the ice.October 16 - 137 days after initial application

I am finally scheduled to fly. We woke up early to weigh all of our bags and persons before a brief video orientation and discussion. At roughly 9 AM, we board the plane and I deploy to the ice.And that's it! Over four and a half months of paperwork from start to finish. However, receiving a rapid response from HR and the hiring manager is unusual, I'm told. I know some people who have applied for years and only just got down for their first season. It all depends on the position, the company you work for, your qualifications, and chance. I'm not a cook in the real world, but it was my opportunity to head down to the ice and I'm grateful to have had this opportunity.

Applying for only three positions and landing one is highly unusual, and if you're really geared to get down here I recommend applying to as many jobs as you can, even if you're not fully qualified for all of them. Recognize that you need demonstrable skill in whatever work you're applying for, but let the hiring manager tell you "no" before you do it yourself. You never know what may happen.

Botanical Resources

- NC State Dendrology

- 2024 Flora of the Southeastern U.S.

- Merlin Bird ID, Cornell University

- ILEX Study Tool for Tree ID

- FloraQuest

Suggested Reading

- A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold

- Silent Spring, Rachel Carson

- American Canopy, Eric Rutkow

- Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Gathering Moss, Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Exploring Southern Appalachian Forests, Drs. Steph Jeffries and Tom Wentworth

- Regarding Willingness, Tom Harpole

- Ice Bound, Dr. Jerri Nielson

- Endurance, Frank Worsley

- Turn Left at Orion, Dan Davis and Guy Consolmagno